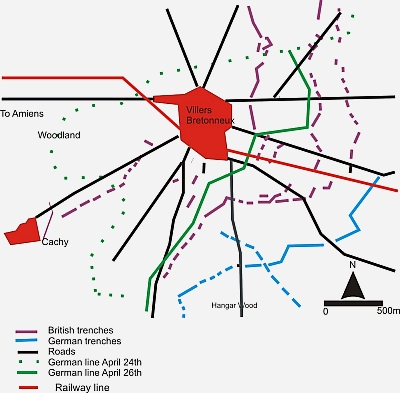

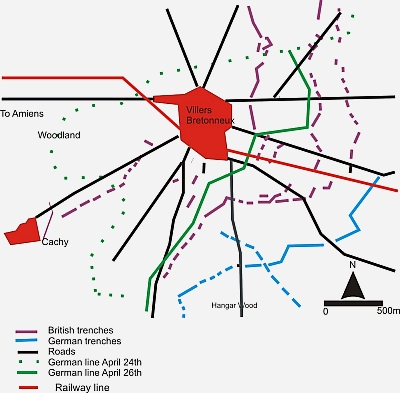

Well, after we had cleared the village, we came across a wounded man. A shell splinter had severed the shinbone completely, leaving him with a broken leg. He had walked some distance in this condition, fixed by two entrenching tools, one on either side of his leg. He was a big and heavy man and we had a rare job with him. Rifles were the only means we had of carrying him. We could only make slow progress though. The enemy was close on us, and I was afraid of them catching a glimpse of such a fine target, as a small group of men would naturally present. So we had to harden our hearts against the groans of the wounded man and get him along regardless of his pain. Fortunately we came across a truck lying at the side of the road, and upon this we placed him and got him safely away. The same night a small party of us came across an officer of the Worcesters and we asked him if he had seen any of our battalion knocking round. He said he hadn’t. So he sent us down the railway cutting, which ran close by. The railway runs through Villers Bretonneaux. What a mess it was in! Absolutely wrecked for several miles by shellfire. There were some old dugouts cut into the bank just where we were in the cutting and in these we placed our guns and ammunition. We had orders to stop any Germans coming down the line. We each took it in turns to do sentry at the door of the dugout, a jolly risky job it was, for the shells kept coming down into the cutting until the metals were all twisted and broken and the sleepers unrecognisable. Down in the dugout we had a man wounded in the leg and head. Four stretcher bearers from the nearest aid post came down to take him away. They reached the dugout in safety and placed him on the stretcher, but they hadn’t walked ten yards when a shell came down and killed all four stretcher bearers and sent the wounded man flying off the stretcher. He hadn’t been touched by the shell, but the concussion had moved him. Well, despite his leg, he got up and ran like the wind. The shock had driven him quite mad, poor fellow.

A day or so after this we came across what a left of our battalion and joined them. A fine mess we were all in. Some of them showed me their rifles with the stocks blown off. Three days later we got relieved by the Australians, and we were pretty glad to get away. Most of us hadn’t had a wash for about a week for one thing, and our feet were in a bad state as well. And so ended my first experience of active service in grim reality.

I must now say a word or two about the conditions we have to live under in France, for although we were out of the line we were by no means comfortable. One never is in France. Now the main trouble amongst the troops is the presence of lice in the underclothing, and also in the seams of the trousers and tunic. These frightful insects, or vermin rather, do more to annoy and make us uncomfortable than anything else. As long as you are on the move they’re not so bad, but immediately you stop to rest or sleep these insects start on you, and many a time I have been unable to sleep at all because of them. The main cause of such vermin being present in our clothes was because a clean change was unprocurable for several weeks sometimes, and there you are in a begrimed state and these insects feeding on you and making you itch terribly. Naturally you scratch and that makes things worse, for you then become subject to awful rashes. These are the conditions the troops live under in France, and I’ve no doubt, in other places as well, and this is the main reason why no soldier wishes to go out a second time once he has seen and felt for himself. It isn’t the fighting we mind. That is what we went out for. But we hadn’t reckoned with these confounded vermin. I may add here that here that when you so get a clean change it looks clean, but examine it, and it’s lousey throughout. It is part of the day’s business in France, fighting the lice. It is the commonest thing to see troops take off their clothing and examine it. Tiresome and rotten job it is too. When one is in action, or during a big battle, and especially during a retreat, of which I have had some experience, the conditions are awful. A wash is a luxury. Sometimes I have been only too pleased to get a swill from a puddle in the middle of the road. And at times like these the food is very uncertain. A word here on the food will not be out of place.

Food Conditions

Rations are dished out every night as far as possible, and usually consist of bread, dog biscuits, and some cheese or jam, if you are lucky. The average ration for one man each day is about a quarter of a loaf, two dog biscuits, and sometimes a pat of margarine. The jam is dished out to sections generally, a section consisting of from twelve to sixteen men. If we are out of the line a stew is served up at dinner and perhaps bacon at breakfast. If we’re in the line tins of ‘macconnachies’. That is, cooked dinners in closed tins are issued, when a hot stew is unobtainable. Bully beef, of course, is common enough, and one soon gets tired of it. At all events, it was the conditions I wished to make as clear as possible. It is frightfully uncomfortable to have to go weeks and weeks in an unclean state. But it can’t be helped and I only wish when I return from France that some munition strikers could have been made to taste it; for they can keep clean, sleep in comfort, and earn a good wage.

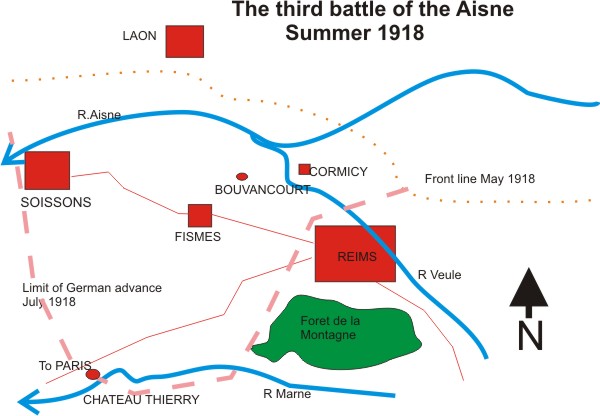

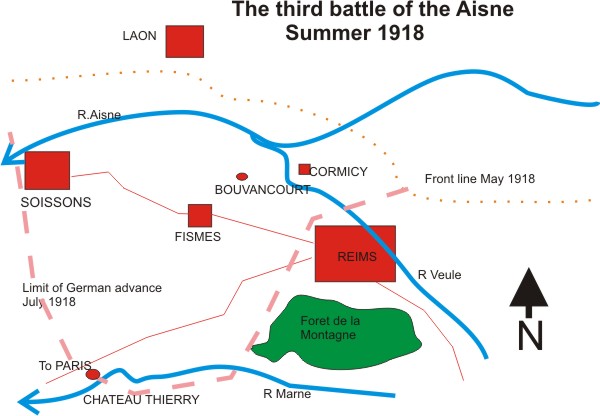

After we had got rested a bit and made ourselves as clean as possible we entrained and made a thirty-six hours’ journey to the south of France. Our division – the 8th, had orders to take over a part of the line from the French in the Rheims-Soissons sector, and, having got up there, we ensconced ourselves in some French billets – some of the best billets I’ve occupied in France. One evening the OC. Coy. sent for the N.C.O.s. He kept us up some time too, explaining and describing what part of the line we were going to take over. We were then situated about eight miles from the line s we had a bit of a march to get there. So on the appointed night we went up and took up our positions. The trenches here were old ones and absolutely infested with rats. The dugouts were the best part. They had been wonderfully well made, some of them a good twenty feet underground. In front there was barbed wire by the ton, and the position we occupied was on a crest, which commanded a fine view. A better position could scarcely have been found, and yet, because this part was quiet they took away most of the artillery and just left a few posts in the line.

A Night Raid

At any rate, here we were, and conditions were not so bad except for the heat. Well for about four days, things went on smoothly, until one evening, about five, I saw our sergeant-major coming down the trench with a notebook in his hand. I knew what he was after. Coming up to me he asked if I would volunteer for a bombing raid that night on the German front line. Now I am a Lewis gun N.C.O., and I wondered at his asking me, for they are not allowed to take Lewis Gun N.C.O.s for raids at all. But for all that, when he asked me I said, “Yes”. My pals were going to chance their arms, so I thought I’d chance mine as well. There were twenty-eight of us altogether and we were each given a number on a slip of paper. Of course mine must needs be thirteen, and I was also first bomb thrower. They took away my rifle and left me with the bayonet alone as an arm. And so at 11 p.m., we went over, all of us in shirtsleeves. The German front line was 750 yards from us so we had some distance to traverse. Well, we had proceeded about five hundred yards when we came across a plank on the ground with four bombs ranged on it in such a manner as to instantly explode and raise the alarm should anyone run into or against it. Of course the Jerries had laid it there for the purpose of letting in some raiding party such as ourselves. But unfortunately for Jerry, we saw and avoided it just in time. Having passed this and we made our way to an old German tank about 150 yards from their frontline. Here we all met, and having made sure that all were present, we began the tedious approach. We found that there were three rows of barbed wire in front of their line, and a very difficult job we found it getting through; silence, you see, was the main factor, and then of course, two of our chaps went and put the cap on things. We had negotiated two rows of wire without being discovered and were just going to attempt the third when these two crawled together in the darkness, collided, and their helmets immediately clanged together just like a gong. By Jove! You could have heard a pin drop after that. The silence was awful. Then we heard a sentry challenge and the very tone of his voice told me that he’d got the wind up right enough. You could hear the Jerries opening the bolts of their rifles and preparing to fire all the way along the line. Next, up shot half a dozen Verey lights which made the place as light as day all at once. With that the Jerries opened fire and the bullets whizzed over us. As for our party, we were all lying pretty low, you can bet, and Jerry soon found out that he wasn’t hitting anything. But he had other means, and I must needs get a right dose of those means for I heard something roll like a stone down the side of the shell hole I occupied. I knew well enough what it was but I had no time to escape. Next instant there was a terrific explosion right on top of me. The concussion shifted me a yard or two. But I wasn’t hit at all, the reason being that the particular type they were using were stick bombs, which comprised a thin casing filled with explosive and a wooden handle by which the bomb was thrown. After this they began sending them over pretty rapidly and the result was that our chaps has to clear out. But they had forgotten all about the barbed wire. Some of them got caught on it, and in their efforts to get away they tore their clothing frightfully. Two of our fellows were shot while struggling in that confounded wire. I wasn’t for hurrying quite so much, and, when things had quietened down a bit I slipped away as quietly as possible, got through the wire and made for the tank, but I could see nothing of my comrades. I then made the best of my way down to our lines where I was hailed with surprise. I had been reported missing and the sergeant-major wasn’t half in a bad way. He must have remembered that my number was thirteen.

At any rate, here we were, and conditions were not so bad except for the heat. Well for about four days, things went on smoothly, until one evening, about five, I saw our sergeant-major coming down the trench with a notebook in his hand. I knew what he was after. Coming up to me he asked if I would volunteer for a bombing raid that night on the German front line. Now I am a Lewis gun N.C.O., and I wondered at his asking me, for they are not allowed to take Lewis Gun N.C.O.s for raids at all. But for all that, when he asked me I said, “Yes”. My pals were going to chance their arms, so I thought I’d chance mine as well. There were twenty-eight of us altogether and we were each given a number on a slip of paper. Of course mine must needs be thirteen, and I was also first bomb thrower. They took away my rifle and left me with the bayonet alone as an arm. And so at 11 p.m., we went over, all of us in shirtsleeves. The German front line was 750 yards from us so we had some distance to traverse. Well, we had proceeded about five hundred yards when we came across a plank on the ground with four bombs ranged on it in such a manner as to instantly explode and raise the alarm should anyone run into or against it. Of course the Jerries had laid it there for the purpose of letting in some raiding party such as ourselves. But unfortunately for Jerry, we saw and avoided it just in time. Having passed this and we made our way to an old German tank about 150 yards from their frontline. Here we all met, and having made sure that all were present, we began the tedious approach. We found that there were three rows of barbed wire in front of their line, and a very difficult job we found it getting through; silence, you see, was the main factor, and then of course, two of our chaps went and put the cap on things. We had negotiated two rows of wire without being discovered and were just going to attempt the third when these two crawled together in the darkness, collided, and their helmets immediately clanged together just like a gong. By Jove! You could have heard a pin drop after that. The silence was awful. Then we heard a sentry challenge and the very tone of his voice told me that he’d got the wind up right enough. You could hear the Jerries opening the bolts of their rifles and preparing to fire all the way along the line. Next, up shot half a dozen Verey lights which made the place as light as day all at once. With that the Jerries opened fire and the bullets whizzed over us. As for our party, we were all lying pretty low, you can bet, and Jerry soon found out that he wasn’t hitting anything. But he had other means, and I must needs get a right dose of those means for I heard something roll like a stone down the side of the shell hole I occupied. I knew well enough what it was but I had no time to escape. Next instant there was a terrific explosion right on top of me. The concussion shifted me a yard or two. But I wasn’t hit at all, the reason being that the particular type they were using were stick bombs, which comprised a thin casing filled with explosive and a wooden handle by which the bomb was thrown. After this they began sending them over pretty rapidly and the result was that our chaps has to clear out. But they had forgotten all about the barbed wire. Some of them got caught on it, and in their efforts to get away they tore their clothing frightfully. Two of our fellows were shot while struggling in that confounded wire. I wasn’t for hurrying quite so much, and, when things had quietened down a bit I slipped away as quietly as possible, got through the wire and made for the tank, but I could see nothing of my comrades. I then made the best of my way down to our lines where I was hailed with surprise. I had been reported missing and the sergeant-major wasn’t half in a bad way. He must have remembered that my number was thirteen.

And so ended my first, and I hope it will be the last bombing raid. On thinking about it afterwards it seemed to me that if the Germans had known that there were as many and twenty-eight of us altogether instead of a small patrol they would have put up a machine-gun barrage, and not one of would have ever got back, but thank Providence it turned out otherwise.

The Retreat on the Aisne

It was a matter of two or three days after this that I was sent out of the line and placed as an instructor on the staff of the 9th Corps Lewis Gun School. I was lucky, that is all, as will be seen presently. I took with me six men of my company to train as Lewis gunners under me, and I often wished I could have had a class of men as good as these every time I took a class through the course. They worked like slaves and I was quite surprised, for the British Tommy is not always so keen to learn, especially the Lewis Gun. I solved the reason though, one day. It appears that they had heard that I was having a shot at a commission and so they decided between themselves to work hard so that I should reap the benefit and credit of having a champion class. Jolly good of them wasn’t it? But all this didn’t last long. One night, A Sunday it was, we suddenly got orders to break up and clear out at a moment’s notice, which we did. There was evidently a big German “biff” pending, and off up to the line we had to go. That night we were sent up on the divisional motor lorries and at three next morning we reached our destination. What a destination too. The place was poisoned with mustard gas, for the Germans had sent over any amount of it during the night behind our lines. While marching up towards the line we wore our masks practically the whole time. We could tell there was a battle on a large scale pending by the tremendous din the guns were making. It was just one perpetual roar. The remainder of our battalion had gone up at 1 a.m., when the bombardment started. I wondered how they were going on. My brother Geoffrey was with them I knew, for I hadn’t seen him since I left the line for the 9th Corps school.

At last we reached out transports, and the gas lessened a good deal. Very soon after an officer who had been with us as the Lewis Gun school was ordered up along with a party of about forty of us, myself included, and we had not proceeded for more than about a quarter of an hour’s walk when we got right into the battle, and from that moment our officer made two or three costly mistakes. Just at the time we were on the main road in full sight of the enemy observation balloons. There was any amount of transport dashing up on the retreat together with civilians retreating before the advancing Germans. Well, the Jerries had the road marked, for they landed shell after shell on or near it. One or two would occasionally land right on a transport wagon. The result was only too obvious. The horses went quite mad; their eyes almost coming out of their heads with fear. They caught a great deal of shrapnel also.

The most heart rending sight, though. Was the wretched French peasantry, struggling along with what they had time to rescue from their property. I can’t describe it. I have no wish to. But just imagine shells falling among little kiddies clinging on to their mothers and half-dead with fright. It had taken some time to put it all down, but I took it all in a few moments as I stood on that shell-stricken road. It was at this juncture that a shell landed about ten yards from us, so we got down in a bit of a ditch by the roadside and as luck would have it, the next shell landed and burst right in amongst us. It killed two instantly and wounded several, myself included. I could have got away with my hurt, but I thought I would stick it as best I could. It was in the right shoulder that I was hit. I managed to work the shrapnel out all right, but I didn’t half suffer for about a week with it. The brace of my equipment kept jarring on it, beside which I was fighting and on the go all the time.

Well, after this the officer thought it about time to shift, and so we cleared out and away from the road. It was just then that I noticed one of our party lying at the side of the road. I thought he was wounded, but when I questioned him he only moaned. He was not wounded at all but absolutely frightened to death. He shivered just like a leaf and I could not get him to come with me for ever such a time. I almost had to drag him along before he would come, but at length I managed to persuade him. I never saw a fellow in such a pitiful state before. I afterwards found out that it was his first time in action and the shells had totally unnerved him poor chap. I took him along with me and joined the rest of our party about half-a-mile away. Our orders were to join the Worcesters if we could find them, which was an impossible job. It was just then that an artilleryman came running up. He seemed to have totally lost himself. Then, in a few words, he told how the rest of his battery and himself had fired point blank into the Germans not twenty minutes beforehand, and how they had been forced to blow up every gun they had in order to prevent the Germans capturing them intact. We gave him a drink, and told him to go back to the rear. After this we got into an old trench on the side of a rise, which overlooked the plain in front of Bouvancourt, and across this plain we could see the Germans advancing, scores and scores of them. We turned our two Lewis guns on to them but it didn’t make much difference. There were so many. And all this time I didn’t see one of our shells burst among them in five minutes. And there we were. Four British divisions against about twenty German divisions and with practically no artillery to back us up. A pretty situation surely! On our right from the trench where we were situated there was a large wood and just in front of this we could see our fellows surrendering and being marched off behind German lines. The Jerries soon discovered our little party and began sending over trench mortars to try and oust us out. But our officer was as stubborn as the ground under him and he wouldn’t budge. At last when one or two fell right in the trench he did clear out, but only to get into a fresh mess. Enemy aeroplanes sighted us and came swooping down on us like hawks. They flew to within a few feet of the ground and opened a deadly fire on us with their machine gins. It was about the most harassing experience I have ever been through. The only thing we could do was run. Two or three of our chaps lay down on the ground, but they got absolutely riddled with bullets. How it was most of us were not hit I don’t know. For one thing we scattered, and I was relieved when at last I reached the shelter of a tree. Several got wounded and the officer had the end of his forefinger taken off by a bullet. It was a case of each man for himself now, I made off at the double down a steep incline carrying one of the Lewis Guns. I didn’t think it worthwhile to stop and be taken prisoner. At the foot of the incline I came across a deserted French store, as far as the original owners were concerned, but two of three Tommies were trying to get the door open. I saw what was wanted and so I got hold of a spade close by and with this implement smashed the lock to bits. We were frightfully hungry and thirsty and you can imagine our delight and surprise on entering. There were tinned stuffs and provisions of all kinds and also three barrels of red wine. We got as much of the provisions as we could carry and then had a drink of the red wine. I’m pretty sure we drank a good quart each. At ant rate, I did, and I’m supposed to be a teetotaller. But by Jove! When we got outside most of us were all over the place directly. I managed to control myself, but anyone could see that I was a bit merry. “Come on chaps”, I yelled, “unless you want Jerry to get you”. Whereupon they tumbled after me and a jolly funny sight we must have looked, I know.

It was not long after this that I found a few of our own battalion. I asked them for news and they told me. It appears that the Germans had got them totally by surprise, for they took our battalion headquarters, the colonel, second-in-command, and nearly two companies prisoners. I asked them if they had seen anything of Geoffrey, but they couldn’t enlighten me. On we went together with transport of all kinds retreating. Oh! It was indescribable. The hot sun burned down on us, the aeroplanes harassed us with bombs and machine guns and what not. Night setting in, we dug ourselves in, the while keeping a sharp lookout. Then it was that the lice started on us. Some of the chaps pretty near went mad with them, and I suffered a good deal. The clothing we then wore we had had for about three weeks past and it has got infested with lice. We were perspiring, too, which made them worse. We hadn’t been dug in long when the alarm was raised and we had to retire again, and so it went on all next day and the day after. Digging in, retiring a bit, and digging in again until we were so fatigued that we hardly knew what to do with ourselves.

With the French

It was on the afternoon of the sixth day that a small party of us fell in with some French, who were dug in front of a large clover patch. For two days, we remained here and all the time the Germans kept shelling us and sending over trench mortars. It was morning about 4 a.m. that an officer who was with us took a sergeant, myself, and six men, and led us out at the double while it was still dark about a hundred and fifty yards in front of the French posts, which then constituted the front line. But he did not stay with us. He just told us to dig in where we were as fast as we could and then left us. So there we were almost on top of the advanced German machine guns. The clover we were lying in was wet through and so were we before long. It was fearfully difficult digging with the small tools we carried and the Jerries soon discovered us. Then came a hot half-hour. Every time we raised our backs so as to get a bit of way on with the entrenching tool they would open fire, and we wouldn’t dare move for the next five minutes. Then they began with trench mortars, and it was at this juncture that the man lying next to me had his left eye taken clean out of his head with a bullet. He immediately threw off his pack and equipment and made off as best he could through the clover. The mortars were now getting jolly dangerous, and I knew if I stayed any longer in that death trap I should very soon get put out. So with caution I made my way back through the wet clover. What a painful journey it was, too. I was carrying my full complement of equipment and ammunition, my pack and rifle, and I was so utterly fatigued that I could hardly get along. On the way back I passed three of my heroic comrades who had been with me. All three had been killed by the mortars. And so it was that I reached one of the French posts and almost fell, rather than got into it. The Frenchmen who was in it gave me some food and drink and I felt better for it. But I wasn’t to remain there long. About two hours after the preceding episode we were driven out of our positions and all that day found us fighting for out very existence. Just on nightfall I found myself with a captain and a corporal of the 25th Division on the edge of a clearing. We were pretty nearly surrounded by Germans, and the clearing was swept with machine gun fire and also it was our only way out. So we all three made a dash for it and got across, luckily, without getting hit. Dear me! We only just escaped. That clearing was in German hands five minutes later. I ran on as fast as I could, but soon fell to walking. Coming to a crossroads I found one of our guns with one wheel shot away and a solitary artillery officer standing near. He had lost all his kit but had stuck to his revolver. I walked down the road with him for some distance. Half an hour later I reached the top of a rise in very bad condition. Not only was I bodily fatigued but my feet were fearfully sore. It was here that witnessed the bringing down of two German observation balloons. A goodly sight it was. They both burst into flames and, of course, became total wrecks in no time.

Enemy Checked

It was at this point in the retreat that we managed to check the oncoming Germans. More reinforcements and guns had been sent up to us so that it gave us a respite for a bit. Next day it was that I met one of our fellows who told me that my brother was not two hundred yards away on top of the rise, a front that then composed the front line. So without more ado I made my way up there and found him. He didn’t half stare at me, and so did I, too. I could hardly recognise him, he was so begrimed and so must I have been. Both of us forgot that we had not had a wash for about eighth days. I remained here that night and the next morning, during which the Germans began shelling us again. During the afternoon, we withdrew again and took up a fresh position along one side of a main road. Here we commenced to make some proper defences, and did so. They soon began shelling again and it was then I witnessed one or two instances of what generally happens when men are totally fed up. They just shoot themselves, and that day I witnessed it. It is a terrible thing but in cases such as these were, it was almost pardonable, poor chaps.

It was at this point in the retreat that we managed to check the oncoming Germans. More reinforcements and guns had been sent up to us so that it gave us a respite for a bit. Next day it was that I met one of our fellows who told me that my brother was not two hundred yards away on top of the rise, a front that then composed the front line. So without more ado I made my way up there and found him. He didn’t half stare at me, and so did I, too. I could hardly recognise him, he was so begrimed and so must I have been. Both of us forgot that we had not had a wash for about eighth days. I remained here that night and the next morning, during which the Germans began shelling us again. During the afternoon, we withdrew again and took up a fresh position along one side of a main road. Here we commenced to make some proper defences, and did so. They soon began shelling again and it was then I witnessed one or two instances of what generally happens when men are totally fed up. They just shoot themselves, and that day I witnessed it. It is a terrible thing but in cases such as these were, it was almost pardonable, poor chaps.

The Germans now received a proper check for fresh artillery and troops had been brought up and we were at last able to stop them. But for a week after that we were still in the line. Our condition was fearful, as you could image. At last, though, we did get relieved. How glad we were to get out after all we had gone through. After we had got out our numbers were very small. We had commenced with a full division of ten thousand men, and now, after the action we couldn’t make up a single battalion. After this we moved down and joined our transport, and two or three days later our divisional commander came along and spoke to us in his usual manner.

A draft of seven hundred joined our battalion, thus making us up to full strength again. The rest of the division was likewise made up in a surprisingly short time, and about two weeks later we got down to the seacoast where we began our training again. It was at this place that Geoff and I decided to push forward with our commissions and so we did, with the consequent result that about three weeks later they came through, and on Tuesday, the 22nd July we sailed for England.

And so ends a narrative which my father wished me to relate, and which I have done at his request; but, for my own part, I am sure I wish to forget all I’ve been through on the Western Front.

[These articles were printed in 'The Darwen News' on March 15th, 22nd and 29th, 1919.]

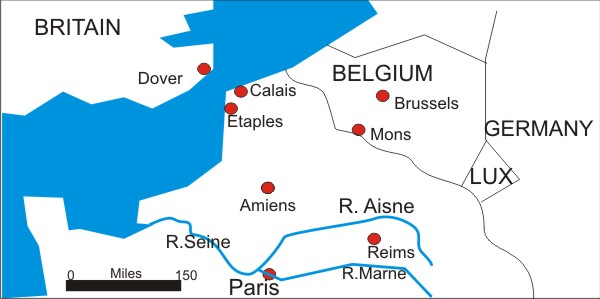

On the night of Good Friday, we travelled down by special train to Dover, and from there we embarked for Boulogne. From here we travelled up to Etaples, the base. An absolutely awful place! Positively frightful! It took about three hours to get a meal, and then you were lucky if you got anything at the end of that time. At meal times it was one terrific push, for there were such crowds at the doors of the dining halls that it was practically impossible to get in, and if you didn’t push you would most likely end up hungrier than ever, not to say perspiring and in no pleasant temper. It was at this place that I was transferred from the Manchester Regiment in which I was then arriving to the 2nd Battalion East Lancashires belonging to the 8th Division. Soon after this we left the base to join our battalion, which in due course we did. Just at the time the battalion was out for a rest after having had a very rough time in the German offensive launched on March 21st.

On the night of Good Friday, we travelled down by special train to Dover, and from there we embarked for Boulogne. From here we travelled up to Etaples, the base. An absolutely awful place! Positively frightful! It took about three hours to get a meal, and then you were lucky if you got anything at the end of that time. At meal times it was one terrific push, for there were such crowds at the doors of the dining halls that it was practically impossible to get in, and if you didn’t push you would most likely end up hungrier than ever, not to say perspiring and in no pleasant temper. It was at this place that I was transferred from the Manchester Regiment in which I was then arriving to the 2nd Battalion East Lancashires belonging to the 8th Division. Soon after this we left the base to join our battalion, which in due course we did. Just at the time the battalion was out for a rest after having had a very rough time in the German offensive launched on March 21st. It was at Passchendaele that this battle took place, the main feature being the shelling. “Beaucoup bombard” as the boys says. Little did I know then what a furious bombardment I was to experience soon after. And so it was that the same day I joined the battalion we moved up towards the line, and on April 18th relieved troops on the left or, I should say, east of the village of Villers Bretonneux, which is a fairly large place situate about ten miles from the city of Amiens. It had been a pretty quiet front for some weeks past, but it was now destined to become a battlefield. For four days we remained in the positions we had at first occupied but at the end of that period we shifted into small posts in front of the village. By small posts I mean small trenches from fifteen to twenty yards in length. There was an interval of about thirty to forty yards between these posts, and, as I shall explain later, it was these intervals that nearly caused me to be taken prisoner, together with some of my comrades. At any rate we had been about twenty-four hours in them when a warning came round that the Germans were about to attack with mustard gas. Mustard gas, I may say, was the kind mostly used by the Germans then, and burns rather than asphyxiates one. Sent over in shells, it is in the form of a liquid until, the shell explodes on contact. The gas thus liberated meets the fresh air and turns into its natural form or vapour and if the atmosphere is quiet it lies about the ground and in shellholes, being heavier than air, and so becomes exceedingly dangerous if anyone happens on it. At all events, we received the warning, but the next morning arrived and the Germans didn’t attack. We made up our minds to a certainty though that they would attack the following morning, so a boy named Ellis and myself conferred, and we decided to have a look round the village and see what we could find in the way of eatables, for we had made up our minds to make a day of it before Jerry opened his attack. It was risky to a certain extent, for the village was under shellfire and at odd intervals one would go smashing through the roof of a house. The first place we came upon was a deserted yard in which we discovered bully beef and biscuits by the ton. We seized about twenty tins of beef and as many biscuits, and then went off to see if there was anything to drink and so to make things complete and every man in our post agreeable. We knew that that the cellars ought to contain something, but we also knew that most of the cellars in the village were full of gas, any amount of gas shell having been sent over into the village. Anyway, we got into a typical looking house and reached the head of the cellar steps. Here we put on gas masks, for we were not chancing anything. The cellar luckily contained no gas, but it contained something else. That something Ellis immediately sampled and pronounced excellent. It was French wine, so we filled a petrol can to take back with us. Petrol tins, I may say, are used for carrying drinking water in France. After this we ascended the steps again, got together the viands, and made our way back to the post, where we were greeted pretty warmly and dubbed good fellows, especially after they had tasted the wine, and for once we really felt satisfied.

It was at Passchendaele that this battle took place, the main feature being the shelling. “Beaucoup bombard” as the boys says. Little did I know then what a furious bombardment I was to experience soon after. And so it was that the same day I joined the battalion we moved up towards the line, and on April 18th relieved troops on the left or, I should say, east of the village of Villers Bretonneux, which is a fairly large place situate about ten miles from the city of Amiens. It had been a pretty quiet front for some weeks past, but it was now destined to become a battlefield. For four days we remained in the positions we had at first occupied but at the end of that period we shifted into small posts in front of the village. By small posts I mean small trenches from fifteen to twenty yards in length. There was an interval of about thirty to forty yards between these posts, and, as I shall explain later, it was these intervals that nearly caused me to be taken prisoner, together with some of my comrades. At any rate we had been about twenty-four hours in them when a warning came round that the Germans were about to attack with mustard gas. Mustard gas, I may say, was the kind mostly used by the Germans then, and burns rather than asphyxiates one. Sent over in shells, it is in the form of a liquid until, the shell explodes on contact. The gas thus liberated meets the fresh air and turns into its natural form or vapour and if the atmosphere is quiet it lies about the ground and in shellholes, being heavier than air, and so becomes exceedingly dangerous if anyone happens on it. At all events, we received the warning, but the next morning arrived and the Germans didn’t attack. We made up our minds to a certainty though that they would attack the following morning, so a boy named Ellis and myself conferred, and we decided to have a look round the village and see what we could find in the way of eatables, for we had made up our minds to make a day of it before Jerry opened his attack. It was risky to a certain extent, for the village was under shellfire and at odd intervals one would go smashing through the roof of a house. The first place we came upon was a deserted yard in which we discovered bully beef and biscuits by the ton. We seized about twenty tins of beef and as many biscuits, and then went off to see if there was anything to drink and so to make things complete and every man in our post agreeable. We knew that that the cellars ought to contain something, but we also knew that most of the cellars in the village were full of gas, any amount of gas shell having been sent over into the village. Anyway, we got into a typical looking house and reached the head of the cellar steps. Here we put on gas masks, for we were not chancing anything. The cellar luckily contained no gas, but it contained something else. That something Ellis immediately sampled and pronounced excellent. It was French wine, so we filled a petrol can to take back with us. Petrol tins, I may say, are used for carrying drinking water in France. After this we ascended the steps again, got together the viands, and made our way back to the post, where we were greeted pretty warmly and dubbed good fellows, especially after they had tasted the wine, and for once we really felt satisfied.

At any rate, here we were, and conditions were not so bad except for the heat. Well for about four days, things went on smoothly, until one evening, about five, I saw our sergeant-major coming down the trench with a notebook in his hand. I knew what he was after. Coming up to me he asked if I would volunteer for a bombing raid that night on the German front line. Now I am a Lewis gun N.C.O., and I wondered at his asking me, for they are not allowed to take Lewis Gun N.C.O.s for raids at all. But for all that, when he asked me I said, “Yes”. My pals were going to chance their arms, so I thought I’d chance mine as well. There were twenty-eight of us altogether and we were each given a number on a slip of paper. Of course mine must needs be thirteen, and I was also first bomb thrower. They took away my rifle and left me with the bayonet alone as an arm. And so at 11 p.m., we went over, all of us in shirtsleeves. The German front line was 750 yards from us so we had some distance to traverse. Well, we had proceeded about five hundred yards when we came across a plank on the ground with four bombs ranged on it in such a manner as to instantly explode and raise the alarm should anyone run into or against it. Of course the Jerries had laid it there for the purpose of letting in some raiding party such as ourselves. But unfortunately for Jerry, we saw and avoided it just in time. Having passed this and we made our way to an old German tank about 150 yards from their frontline. Here we all met, and having made sure that all were present, we began the tedious approach. We found that there were three rows of barbed wire in front of their line, and a very difficult job we found it getting through; silence, you see, was the main factor, and then of course, two of our chaps went and put the cap on things. We had negotiated two rows of wire without being discovered and were just going to attempt the third when these two crawled together in the darkness, collided, and their helmets immediately clanged together just like a gong. By Jove! You could have heard a pin drop after that. The silence was awful. Then we heard a sentry challenge and the very tone of his voice told me that he’d got the wind up right enough. You could hear the Jerries opening the bolts of their rifles and preparing to fire all the way along the line. Next, up shot half a dozen Verey lights which made the place as light as day all at once. With that the Jerries opened fire and the bullets whizzed over us. As for our party, we were all lying pretty low, you can bet, and Jerry soon found out that he wasn’t hitting anything. But he had other means, and I must needs get a right dose of those means for I heard something roll like a stone down the side of the shell hole I occupied. I knew well enough what it was but I had no time to escape. Next instant there was a terrific explosion right on top of me. The concussion shifted me a yard or two. But I wasn’t hit at all, the reason being that the particular type they were using were stick bombs, which comprised a thin casing filled with explosive and a wooden handle by which the bomb was thrown. After this they began sending them over pretty rapidly and the result was that our chaps has to clear out. But they had forgotten all about the barbed wire. Some of them got caught on it, and in their efforts to get away they tore their clothing frightfully. Two of our fellows were shot while struggling in that confounded wire. I wasn’t for hurrying quite so much, and, when things had quietened down a bit I slipped away as quietly as possible, got through the wire and made for the tank, but I could see nothing of my comrades. I then made the best of my way down to our lines where I was hailed with surprise. I had been reported missing and the sergeant-major wasn’t half in a bad way. He must have remembered that my number was thirteen.

At any rate, here we were, and conditions were not so bad except for the heat. Well for about four days, things went on smoothly, until one evening, about five, I saw our sergeant-major coming down the trench with a notebook in his hand. I knew what he was after. Coming up to me he asked if I would volunteer for a bombing raid that night on the German front line. Now I am a Lewis gun N.C.O., and I wondered at his asking me, for they are not allowed to take Lewis Gun N.C.O.s for raids at all. But for all that, when he asked me I said, “Yes”. My pals were going to chance their arms, so I thought I’d chance mine as well. There were twenty-eight of us altogether and we were each given a number on a slip of paper. Of course mine must needs be thirteen, and I was also first bomb thrower. They took away my rifle and left me with the bayonet alone as an arm. And so at 11 p.m., we went over, all of us in shirtsleeves. The German front line was 750 yards from us so we had some distance to traverse. Well, we had proceeded about five hundred yards when we came across a plank on the ground with four bombs ranged on it in such a manner as to instantly explode and raise the alarm should anyone run into or against it. Of course the Jerries had laid it there for the purpose of letting in some raiding party such as ourselves. But unfortunately for Jerry, we saw and avoided it just in time. Having passed this and we made our way to an old German tank about 150 yards from their frontline. Here we all met, and having made sure that all were present, we began the tedious approach. We found that there were three rows of barbed wire in front of their line, and a very difficult job we found it getting through; silence, you see, was the main factor, and then of course, two of our chaps went and put the cap on things. We had negotiated two rows of wire without being discovered and were just going to attempt the third when these two crawled together in the darkness, collided, and their helmets immediately clanged together just like a gong. By Jove! You could have heard a pin drop after that. The silence was awful. Then we heard a sentry challenge and the very tone of his voice told me that he’d got the wind up right enough. You could hear the Jerries opening the bolts of their rifles and preparing to fire all the way along the line. Next, up shot half a dozen Verey lights which made the place as light as day all at once. With that the Jerries opened fire and the bullets whizzed over us. As for our party, we were all lying pretty low, you can bet, and Jerry soon found out that he wasn’t hitting anything. But he had other means, and I must needs get a right dose of those means for I heard something roll like a stone down the side of the shell hole I occupied. I knew well enough what it was but I had no time to escape. Next instant there was a terrific explosion right on top of me. The concussion shifted me a yard or two. But I wasn’t hit at all, the reason being that the particular type they were using were stick bombs, which comprised a thin casing filled with explosive and a wooden handle by which the bomb was thrown. After this they began sending them over pretty rapidly and the result was that our chaps has to clear out. But they had forgotten all about the barbed wire. Some of them got caught on it, and in their efforts to get away they tore their clothing frightfully. Two of our fellows were shot while struggling in that confounded wire. I wasn’t for hurrying quite so much, and, when things had quietened down a bit I slipped away as quietly as possible, got through the wire and made for the tank, but I could see nothing of my comrades. I then made the best of my way down to our lines where I was hailed with surprise. I had been reported missing and the sergeant-major wasn’t half in a bad way. He must have remembered that my number was thirteen. It was at this point in the retreat that we managed to check the oncoming Germans. More reinforcements and guns had been sent up to us so that it gave us a respite for a bit. Next day it was that I met one of our fellows who told me that my brother was not two hundred yards away on top of the rise, a front that then composed the front line. So without more ado I made my way up there and found him. He didn’t half stare at me, and so did I, too. I could hardly recognise him, he was so begrimed and so must I have been. Both of us forgot that we had not had a wash for about eighth days. I remained here that night and the next morning, during which the Germans began shelling us again. During the afternoon, we withdrew again and took up a fresh position along one side of a main road. Here we commenced to make some proper defences, and did so. They soon began shelling again and it was then I witnessed one or two instances of what generally happens when men are totally fed up. They just shoot themselves, and that day I witnessed it. It is a terrible thing but in cases such as these were, it was almost pardonable, poor chaps.

It was at this point in the retreat that we managed to check the oncoming Germans. More reinforcements and guns had been sent up to us so that it gave us a respite for a bit. Next day it was that I met one of our fellows who told me that my brother was not two hundred yards away on top of the rise, a front that then composed the front line. So without more ado I made my way up there and found him. He didn’t half stare at me, and so did I, too. I could hardly recognise him, he was so begrimed and so must I have been. Both of us forgot that we had not had a wash for about eighth days. I remained here that night and the next morning, during which the Germans began shelling us again. During the afternoon, we withdrew again and took up a fresh position along one side of a main road. Here we commenced to make some proper defences, and did so. They soon began shelling again and it was then I witnessed one or two instances of what generally happens when men are totally fed up. They just shoot themselves, and that day I witnessed it. It is a terrible thing but in cases such as these were, it was almost pardonable, poor chaps.