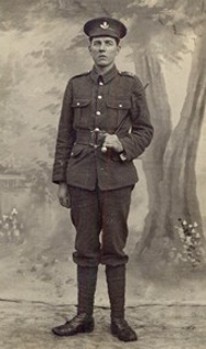

Lance Serjeant, [10983] 5th Bn., King's Shropshire Light Infantry

1901 Census: Living at Tilley Green with parents and siblings: Ada Anna (b. 1888), Ethel Elizabeth (b. 1890), Herbert Harry (b.1893), Elsie May (b. 1898) and Archibald Gordon (b.1900). Ada and Ethel were born in Tilstock, Shropshire and the others were born in Wem.

In 1911, Howard Bromley was working as a cowman at Tilley Hall Farm.

Henry Bromley's parents were Thomas (b. 1816, in Smethcott, Shropshire) & Elizabeth (b. 1835, in Alston, Shropshire).

As soon as it became clear that WWI was not going to be over by Christmas 1914, and that more soldiers would be needed for the Front, a number of fresh battalions were created to aupport the war effort. The 5th Battalion of the Kings Shropshire Light Infantry was the first of many such units.

Howard John Bromley went into Wem and in the patriotic fervour of the time enlisted into the army, along with a number of his friends, determined to do his part for King and Country. He was sent to the depot at Shrewsbury, and from there on to Blackdown Camp, Aldershot, to join ĎBí Company of the newly formed 5th Battalion.

On 23rd. January 1915, the unit was inspected by Lord Kitchener and a high ranking French general. No greatcoats were worn by the troops in order that their excellent equipment could impress the French, but it snowed all the time and the cold was bitter. In March there was another inspection at Aldershot, this time by the King and Queen themselves, under more pleasant circumstances.

On 23rd. January 1915, the unit was inspected by Lord Kitchener and a high ranking French general. No greatcoats were worn by the troops in order that their excellent equipment could impress the French, but it snowed all the time and the cold was bitter. In March there was another inspection at Aldershot, this time by the King and Queen themselves, under more pleasant circumstances.

When basic training was complete, the battalion was placed on a war footing and an advance party sent ahead to France, followed shortly by the main unit, a total of 28 officers and 797 men. On May 20th 1915, Johnís unit landed by troopship at Boulogne and was taken by train to the French town of Cassel. They then marched on to the large camp at Erkelsbrugge. At this camp, which acted as an assembly point and allowed the battalion to regroup and resupply, final hurried training was carried out to prepare the men for their first taste of action. They learnt all that they could about life and discipline in the trenches, and the regular routine of the patrols, and the continual digging that always had to be done. Within 10 days, the unit was sent into action in the northern sector of the Ypres salient. The war had by now stagnated into a war of attrition with both sides bogged down in their trenches, living a nightmare existence in conditions of indescribable filth and terror, far removed from the tranquil life that John had known on the farm at Tilley.

His unit was initially based around Brandhoek and whilst in this area they worked a routine of 4 days duty in the Front Line trenches, followed by four days so-called Ďrestí in the Reserve Line. In reality the reserve tranches were not that far removed from the Front to allow rapid reinforcement in the event of an attack.

On June 16 1915, the Battalion was one of several units ordered to attack the German trenches at Bellewaerde, and this was where the real fighting began. His company was dug in on the Ypres-Roulers railway line while the British bombardment went on. As this finished they moved forward to support the centre of the assault, but very heavy German fire from Hill 60 caused chaos, and the various platoons soon lost touch with each other and became disorientated. Several ended up in a trench near the Menin Road which was already packed with other troops taking part in the attack. Fortunately the German fire was not well directed at this target and eventually ĎBí Company was able to sort itself out to some degree and obey the order to withdraw, though this was hazardous due to the open nature of the ground and there were a number of casualties.

After a short rest at Vlamertinghe the Battalion went back into the trenches near Ypres. On the 25th. June, there was another brief respite for 2 weeks at Zwynland, when they were able to enjoy the fine warm weather. This period would have been more restful had it not been for the continual nightly routine of trench digging. Parties went up to near the front in camouflaged London buses, and had to return before the short night was over in case the Germans spotted them. In mid-July, Johnís Company moved into the town of Ypres, which had now come under German bombardment, and took up reserve positions in the ramparts. Every night their task was to carry the rations and supplies up to the front line, a dangerous task through flooded communication trenches. More fierce fighting followed at Hooge chateau. The chateau had been blown up by a huge mine and the crater then occupied by British troops. On 30th July the Germans attacked and captured the crater. Attempts to counter attack were not at first successful. The unit, together with 2 other companies moved to the front line and held the position for 4 days. They were relieved by reinforcements on August 4th, but returned to the trenches around Railway Wood on the 6th. Shelling by the Germans was continuous for 3 days. Eventually the crater was recaptured, and the battalion moved back to Vlamertinghe to recuperate. Over one quarter of the battalion, some 220 men, had been killed or wounded by the end of August 1915.

Various short tours followed, alternating with rest periods, until September 24th, when the battalion moved up to Ypres by train and entered the trenches at Railway Wood. They were to mount an attack in order to prevent any German reinforcements from the north being sent to help the enemy in the battle of Loos, which had just begun. After 24 hours of continual bombardment and counter bombardment, the battalion attacked and succeeded I capturing two lines of enemy trenches. However the units on either side were not so successful, and the exposed flanks made the position untenable. When the Germans counter-attacked, the company was forced to withdraw right back to where it had started, where they were then shelled by the Germans for the rest of the day. Another 48 men were killed in this action and many were wounded or missing, though a number of the missing did appear later, after wandering about for several days. The Corps Commander congratulated the battalion on its bearing during the battle, and told them how they had kept German troops away from the Loos offensive further south.

Autumn turned into a bitterly cold and wet winter. Incessant rain was turning the ground into liquid mud, and all the shell holes filled with water. The dull and deadly routine continued. Between 15th. November 1915 and February 10th. 1916, the battalion suffered a steady trickle of casualties, losing 43 soldiers, with a further 89 injured. Howard John was now a Lance-Sergeant, and much liked and respected by the officers and men he worked with. At Christmas 1915, there was a brief respite from the horrors of war when the battalion was moved to billets at Houtkerque, for a short spell of leave. In the New Year, however, Johnís unit was sent straight back to Brandhoek again, to their water-logged trenches in the Ypres salient.Though it was a comparatively quiet time, there was the ever-present threat of shellfire and of snipers, who went about their deadly business of picking off anyone who showed their head above the parapet. As night fell both sides would try to repair their trenches as best they could. Although the shelling did not normally cease, small parties working under cover of darkness would be sent out to repair the holes blown in the barbed wire entanglements.

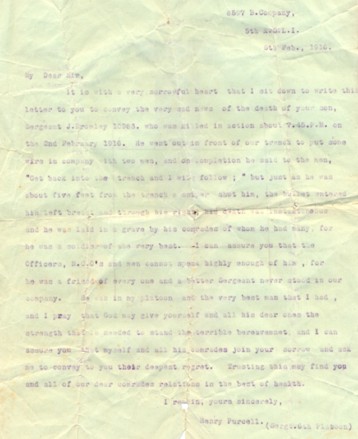

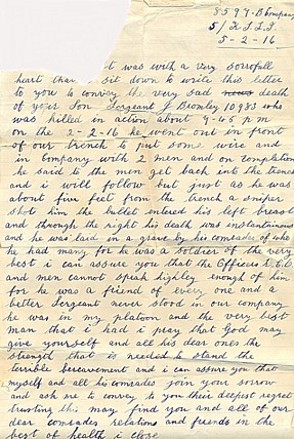

In the early evening of Feb 2nd 1916, John led one such party into No-Manís Land to lay some fresh wire. They had completed their task and were returning to the trench when a German sniper, alerted by the voices, and possibly with the aid of light from a starshell, opened fire, killing Howard John with a single shot. His body was recovered and buried in a small makeshift cemetery nearby. He was only 21 years old. His friend and colleague, Henry Purcell wrote the accompanying letter to Howard Johnís father a few days later in the comparative safety of the reserve line. [See copies.]

As the battle of Ypres intensified, the area was overrun and the burial ground completely obliterated by gunfire. His grave was not located again. He is commemorated on the War Memorial in Wem as Lance Sgt H. Bromley and his name is also engraved on the Menin Gate.